- Home

- Calder Szewczak

The Offset Page 2

The Offset Read online

Page 2

Beyond the edge of the square there is a strip of wild grassland that once served as a road. Miri stumbles through it, beating aside the ragweed, thistles and yellow toadflax to scatter the air with clouds of dry, shrivelled seeds. Standing half-submerged in a dense thicket of blood-red filterweed is an old bus stop; a rusted metal frame is all that remains of the modest shelter. Miri lowers herself onto the rickety bench and takes a few deep breaths, stuffing her fists into her pockets. In one pocket is the crumpled flyer and in the other a folded postcard, a willing reply to Miri’s request to meet at seven the following day, in the cool of the evening. It’s from someone they call the Celt, a woman who she got to know in the volunteer-run ReproViolence Clinic out by the Soho tenements. Although she hasn’t had cause to return there in the last few months – not since she recovered from that last bout of pneumonia – she finds her thoughts turn to the Celt with increasing regularity. Just thinking about her now, she can feel the blood begin to pound in her ears. Miri’s not sure how she ever worked up the courage to ask the Celt to meet. She’s glad she did, though. The chance of seeing the woman so soon is enlivening and fills her with anticipation.

Just then, a flash of movement catches her attention and snaps her out of her reverie. Leaning forward, she warily eyes the patch of filterweed. For a moment, everything is perfectly still. Then the weeds shiver in the windless air. There’s another loud rustle and now she’s sure that something is headed her way through the undergrowth. Tensing, she recalls the swarms that have plagued the city in years gone by – species of all kinds either fleeing fire, flood and famine, or simply surging unchecked with every new imbalance wrought in the food chain.

A rat darts out from the undergrowth and then sits back on its haunches, nose twitching. Miri notices at once the fleshy protuberance that stands proud of the creature’s matted white fur, running like a ridge along its back: a human ear spliced into its spine. In all other regards, it is a perfectly ordinary white rat, with pink feet and a long scaly tail. Miri laughs, partly in relief. She’s been half-braced for the harbingers of a carrion-beetle swarm, but after all that it’s only a rat, no doubt escaped from some nearby laboratory.

“Hello,” she says, stooping to lower her hand towards the creature. Tentatively, it noses at her fingers, its whiskers tickling her skin. Then it clambers up onto her palm, the ear on its back rigid like a sail. She lifts the thing up onto her lap and makes a maze of her hands for it to run through. It seems to know better than she does what her next move will be.

Although she guesses a laboratory rat would probably be used to humans, she is astonished by how much it appears to trust her. It makes no bid for freedom and seems quite content in her company.

Perhaps it thinks you’re an escaped lab rat too, says the voice in her head, which she ignores. Probably the creature is from a long line of animals bred for the trait of docility. Yes, that vaguely chimes with what little she recalls of her halfforgotten genetics lessons. Assuming she’s right, she doesn’t see how a creature so tame could possibly have escaped of its own accord. The only other explanation is that the thing was set free. This is, she thinks, a cruel trick to play on such a beast. It won’t survive the London wilds for long.

While she supposes that a docile lab rat would be more useful for experimental purposes than an aggressive one, she can come up with no good explanation for the human ear growing on its back. Try as she might, she cannot see the utility of it and suspects that it has been done for the oldest of reasons: simply because it is possible.

It’s hardly the first time a genetic experiment has got out of hand. The crimson filterweed that surrounds the bus stop is a case in point. Although the intention was to create a super-strain of knotweed capable of filtering small amounts of carbon – and so improve the local air quality – the plant spread more aggressively than anticipated and spawned several new mutations, overwhelming other flora in the process. Worst of all, its effect on local air quality proved negligible. Several of its later variants seemed not to sequester carbon at all.

Idly stroking the rat, Miri stares out at the square. Now that the pigsuits have dealt with the fire, the crowd is beginning to disperse, surging down the arterial lanes that feed the square in clots of twos and threes.

Someone peels away from the crowd and heads towards her. It’s a boy, a few years older than her, with a strong brown face and a crop of curly hair, an anti-natalist dazzle-pattern scarf pulled down beneath his chin. She recognises him at once as the figure who approached her before. Seeing him again, Miri notices that there’s something in his bearing, in his artfully crumpled stretch suit, that reminds her of the kind of people she grew up with. As he draws near, her fingers twitch. It’s all she can do to stop herself from slipping back into that repetitive gesture of finger over thumb. She knows instinctively that she must not, that it invites attention, that it makes her appear vulnerable; an easy target. To steady herself, she closes her hands tighter on the rat, taking comfort from the warmth of its fur and the strange feel of the ear’s helix against the skin of her palm. Then the rat squirms and she becomes suddenly aware of how small and fragile its skeleton feels beneath her fingers. She loosens her grip.

“Alright?” says the boy, now a few feet away.

Miri tenses herself, ready to run. Seeing this, he stops, and raises his hands in the universal sign of peace. On his face is a blank expression that she can’t read.

Miri switches to the defensive. “Your parents know you’re an anti-natalist, do they?” she asks pointedly.

“Parent,” he corrects her in a languid tone. “One of my dads died when I was a kid.”

Miri chews on this, thinking, no Offset – good for you. All the while, the boy’s eyes search her face. After a moment, his lips curve upwards with a triumphant smirk. “It is you!” he exclaims.

Miri’s stomach drops. She isn’t used to being recognised these days. There isn’t much left of the girl who used to feature so frequently alongside the famous Professor Jac Boltanski in the news clips and promotional materials that document nearly every aspect of her mother’s work.

Though Miri hasn’t had much cause to look in a mirror since she left home, that doesn’t mean she hasn’t noticed how her body has changed. Two years of being constantly on the move and never knowing for sure where the next meal would come from makes a mark on a person. She is skinnier than she ought to be, ribs and collarbone pronounced and visible beneath her skin, which is so pale as to be almost translucent. Despite her gaunt frame, her stomach is constantly bloated, hanging low and distended, and her feet and ankles often swell dramatically, filling with fluid that puffs them to twice their usual size. She is always cold, even in the midday heat. A few months back, she found a heavy cable-knit jumper in an abandoned tip and she has barely taken it off since, even though it is threadbare and smells faintly of urine. There are sores on her face, chest and back. Her hands, once soft and delicate as befitting her cloistered upbringing, are rough with callouses and her fingernails are torn to the quick. Her hair, which she wears short and streaked through with bright reds and oranges, hangs in greasy ropes about her face and is beginning to thin. She wonders what it would take to completely erase her genetic inheritance and every trace of her mothers: Jac’s hard features and Alix’s freckles.

“What are you doing here on your own?” asks the boy when she doesn’t respond.

“None of your business.”

“Your life is everyone’s business.”

Miri closes her eyes. He’s right, in a way.

She gets up to leave but he grabs her thinning arm with enough force to bruise. She catches the smell of lemongrass, an expensively synthesised scent of the kind that often graced a home just like hers. The home that used to be hers.

“Hey – tell me who you’re going to choose–”

Before he can continue, his words give way to a sudden howl of pain. He snatches his hand away as though it has been scalded and clutches it to his chest, peerin

g down to examine where there are now two deep punctures in his skin, the red-wet marks of an animal bite.

Angry now, his dark eyes search out the cause of his pain and he finally sees the white rat, clambering down the leg of the bench. The boy lunges for it, set – Miri is certain – on grabbing the rat by the tail in order to smash its skull against the side of the shelter. Miri tries to block his path but the effort is needless, for no sooner has she scudded forward than the boy falls back, his face twisted in alarm and disgust. Miri follows his gaze and realises that he is seeing the ear half-sunk into the rat’s back for the very first time. Judging from his expression, it’s a sight he finds deeply abhorrent. It transfixes him for a moment and then he tears his eyes away, staggering back and shooting Miri a last, horrified look. Steadily, Miri releases a breath she didn’t realise she’d been holding and then, for good measure, makes the sign again. Finger, thumb, finger, thumb. The rat on the ground at her feet now sits back on its haunches and begins to clean its long pink tail.

The boy is already out of sight, but his words ring in Miri’s ears for a long time after.

Tell me who you’re going to choose.

It’s the question the whole world is waiting to be answered. They won’t have long to wait. Miri’s Offset is in two days’ time.

02

Several hundred miles away, Professor Jac Boltanski is busy cross-checking a long list of figures. She is on a train to Inbhir Nis. A compact overnight bag sits at her feet, the top edge of a heavy, battered lab book poking out above the zip. Papers are strewn across the fold-down table in front of her, each one bearing a different graph or table of measurement. Her catlike green eyes dart between them, lighting upon patterns of significance that would be invisible to anyone else.

After a moment, she gives a low snarl of frustration and leans back in her seat, letting her gaze fall to the window. As she does, the train hurtles into a tunnel and, for a moment, all she can see is herself in the fleeting black mirror. She catches an impression of dark hair cut short, of hard features and sharp cheekbones, and admires the elegant lines of the tailored white shirt she wears buttoned to the throat. Then the train exits the tunnel and she disappears, her reflection replaced by passing fields of stout pink banana trees.

In the last few years, the countryside north of London has become unrecognisable to her. New and unfamiliar industries have sprung up as the people of the Federated Counties have sought to adapt to the fast pace of change occasioned by climatic and political violence.

Some sights Jac can explain. The fields of bright orange corn, for instance, are the legacy of a genetic-engineering project which, as she recalls, was to develop crops that produce higher levels of beta-carotene, the intention of which was to combat vitamin A deficiencies in poorly nourished populations and reduce the risk of sunburn in pale-skinned northern Europeans. The project was not without success, but it transpired that high beta-carotene diets also had the alarming side effect of giving lighter skin tones an orange hue. This, at least, accounts for the startling appearance of some of the people she sees crowded on station platforms as the train hurtles past. What she can’t explain is why so many of them wear purple face masks. They look like the kind designed to inhibit air-borne diseases, but she’s not aware that any of the Counties are on high alert for infection. She supposes instead that the masks could be related to the outbreaks of gang warfare that so often plague the middle Counties, though what exact allegiances they signify she cannot say.

Her mind races ahead along the tracks. She is making for what most folk this side of the border still call Inverness, but which she – out of respect for her Alban colleagues – dutifully refers to in all official communications by the Gaelic name of Inbhir Nis. The Borlaug Institute, of which she is the Director, maintains a testing facility there and, although she is personally accountable for its operation, it has been many years since she visited. It’s not that she intentionally avoids such visits, it is simply that the majority of her time is already spoken for. For the best part, she is bound to London, where she oversees the teams in the laboratory there. In truth, that is but a small portion of her work. In many respects, her job is as diplomatic as it is managerial. She liaises with governors and scientific organisations, and she courts those with the wealth and power that enables their vital work to continue. As much as she might wish it were otherwise, London is where that power lies, so that is where she focuses her efforts.

Although there have been the occasional cursory visits over the years whenever she could squeeze them in, the last time she really remembers being at the Inbhir Nis facility is when Project Salix began, more than eighteen years ago. It was from there that she remotely oversaw the first round of willow planting in the ARZ – the Arctic Remedial Zone – and, in the course of doing so, became the face of the project that would save the Earth. Project Salix, the op-ed headlines had run: Making carbon neutrality a reality. The articles were of a kind: all fawning, all spiked with the same jargon (“advanced phytogenetics” and “secure-system telerobotics”), all carrying Jac’s picture.

The planting itself, hailed as a world-saving rescue mission on an unprecedented scale, was highly celebrated, beamed out to whoever could access it. All over the world, people crowded around what few televisions and computers remained – like pilgrims huddled in the night around the embers of a dying fire – to see Jac give a rousing speech from the testing facility while, out in Greenland, the first trees were planted. Robotically, of course, given that no human could set foot within the ARZ. Everyone who saw it still remembers the fire in Jac’s voice, and how her loving wife Alix stood by her side, a small bundle cradled in her arms.

“This is for my daughter,” Jac said, placing an arm around Alix’s shoulder as, a thousand miles away, the saplings were set into the earth. “This is for us and all who come after: the children of the Arborocene.” It was, several well-wishers assured her, an electric moment, bristling with hope and confidence.

In all the years since, Jac has dedicated her every waking moment to the project, never once doubting that it will be successful. They have now planted every inch of Greenland with Project Salix trees, genetically engineered to be radiation-hard and thereby transforming the nuclear wasteland of the ARZ into a set of branching lungs that draw in carbon dioxide and emit oxygen at an accelerated rate, the world’s first and only hypernovaforestation. By all accounts, it is a triumph: already the Borlaug taskforce has seen year-on-year decreases in global carbon emissions. Not that failure was an option. Of all the concerted efforts to prevent the heat death of the planet, only Project Salix ever had a hope of succeeding. Its effects, combined with those of the Offset, are set to restore the planet’s atmosphere to good health. It is an almost unthinkable eventuality, but maybe – one day – they will no longer need the Offset.

No sooner has she voiced this to herself than she dutifully sets the thought aside. They will always need the Offset; they will always need a check on the human tendency for wanton procreation. There could be no return to the unbridled behaviour of the past, not when that was precisely what had landed them here in the first place and what could so easily overwhelm the planet once more. And, anyway, the Offset was about far more than protecting the environment. Even if her Offset were two years away instead of two days, Jac would still feel the same deep need to level things off with their daughter, to atone for what she and Alix had done.

With a slight shake of the head, she knocks the idea aside and, at last, turns her attention back to the sheaf of papers spread out across the table; the report is one that she has personally compiled out of data drawn from both the London laboratory and the Inbhir Nis facility. Her eyes fall on one figure she took down that morning. Global Average: 500 ppm. It’s the latest CO2 level and exactly on track according to the projections, which should provide some comfort. But Jac is uneasy. Elsewhere, the pages are littered with asterisks and question marks in neat green ink. Each one indicates a statistical variation t

hat, while not beyond the range of the project’s parameters, she cannot fully explain. And she needs an explanation. Now more than ever.

03

Calmer now the square has emptied, Miri reluctantly drops the rat back into the long grass and sets off for the shrine. Though she longs to escape the danger of the city centre, she’s come this far; she’s seen the Offset through to its end, she can’t turn back now.

The shrine is a short walk away, not far beyond the northeast corner of the square. When she reaches it, she finds the place deserted, the only guard a weathered block of Portland stone. A sleeping infant has been carved into the surface, a thick cable of umbilical cord twisting around one ankle, chaining it to the rock. There is a weathered inscription on the sculpture’s base: To light a candle is to cast a shadow.

The tall door beyond is unlocked and creaks noisily on its hinges as Miri enters. She doesn’t bother to pull it closed. Stepping further into the stone mausoleum, she hugs her arms across her chest to still a shiver. Once a church, the entire shrine has a dusty, unused feel to it. There are no flowers or candles by any of the plaques. Little wonder. The shrine dates back from when most considered the Offset to be a noble sacrifice. The memorials were intended to stand as testament to the bravery of those who gave their lives for the good of all. Now they are nothing so much as a malediction on those selfish enough to breed.

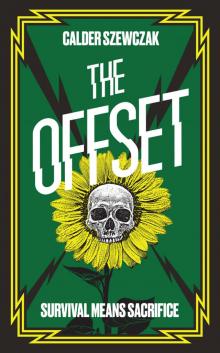

The Offset

The Offset